NIETZSCHE’S ANTI-CHRISTIAN PHILOSOPHY

NIETZSCHE’S ANTI-CHRISTIAN PHILOSOPHYReligion’s victims eventually come to hate life itself—not just themselves. —Nietzsche

A couple of quarters ago, I took a course in Continental Philosophy—existentialism, that is, as distinct from American pragmatism. I am no philosopher, but I am and have been an atheist for quite some time. I don’t know how anyone can still believe there’s some great power in the heavens who watches over them unless they are already defeated and broken in spirit and can no longer rely on themselves. In short—if life isn’t working out for you, then go ahead and imagine there’s someplace else (an afterlife) where poor little you will come out on top.

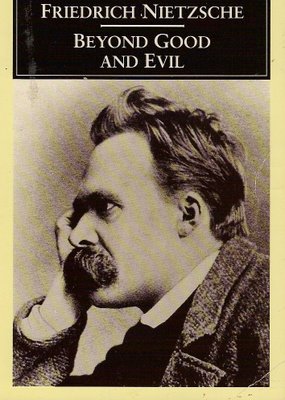

In Continental Philosophy: a critical approach (pp. 121-123), William Schroeder summarizes some of Nietszsche’s reasons for being the atheist he is. They’re good reasons, one and all, and I imagine that few atheists arrive at their own conclusions with having thought or read of these ideas in their philosophical development from superstitious pie-in-the-sky thinker to solid pragmatist and skeptic:

“Nietzsche contends that most religions—especially Christianity—displace the inherent value of acting nobly, encouraging people to act ethically only to achieve some reward (entrance into heaven) and to resist evil only to avoid horrible punishment (hell). Nietzsche believes that such incentives undermine ethical action because it should be indifferent to rewards and punishments. Moreover. the otherworldly focus of most religions encourages adherents to ignore this world—to abandon their responsibilities and ignore their failures here—because they can be compensated or forgiven in the next world. Equally suspect is the belief that a last-minute conversion can atone for a lifetime of heartlessness and lassitude, as if deathbed conversions can eliminate responsibility for such failings. For these reasons, Nietzsche believes most religions mock ethical seriousness because they undermine its presuppositions: that virtue is its own reward, that this world is where ethical action is needed, and that every action matters.

“In addition, many religions idealize asceticism—opposing natural human impulses, e.g., sex, pride, self-assertion. and joy in achievement. Nietzsche thinks these natural impulses are incipient sources of excellence. Religion's primary tactic is to extirpate or annihilate them, producing people who are either divided within themselves (insofar as they maintain some identification with their impulses) or hate themselves (because they cannot overcome them). Self-contemptuous people reject life and act spitefully. When others reciprocate, anger, hatefulness, and resentment escalate, creating poisonous social relations. Religion’s victims eventually come to hate life itself—not just themselves. Nietzsche also challenges Christianity's embrace of "slavish" values—values that sustain the weak, the failures, the inept, and the memocre. Nietzsche holds that the concept of "good" within a slavish system of evaluation is derivativedefined solely in opposition to whatever it calls "evil"—and that "evil" maligns noble traits that enhance human flourishing and exceptional achievement. Slavish value systems sanctify humility, passivity, pity, lassitude, dependence. Nietzsche believes that the best relationship to natural passions is sublimation—redirecting and guiding them toward higher goals. Nietzsche celebrates these impulses because they provide the energy necessary to achieve greatness.

“Beyond this, Nietzsche shows that Christianity's emotional ambiance is dominated by sin, guilt, suffering, penance, atonement, and despair. Thus. its psychic landscape is desolate, without vitality, passion, light-footedness, or playfulness—characteristics that Nietzsche believes are essential to higher achievements, This emotional ambiance devastates the faithful. shattering their self-confidence and inspiration, Moreover, historically, religion is responsible for many ethnic wars and hatreds, and soldiers (and terrorists) infused with holy righteousness are more efficient killers. Of course, priests might argue that religion offers "metaphysical comforts" to the masses, making their modest lives meaningful and providing them with hope. But Nietzsche often thinks that illusory hopes are problematic and that religious meaning depends on indefensible assumptions. Without metaphysical comforts, people would be forced to push themselves to achieve meaningful lives. Nietzsche concludes that the psychological and historical consequences of theism have reduced humanity's capacities for excellence. The demise of such a corrupting institution should be greeted with joy.

“Nietzsche also challenges Christianity's embrace of "slavish" values—values that sustain the weak, the failures, the inept, and the mediocre. Nietzsche holds that the concept of "good" within a slavish system of evaluation is derivative, defined solely in opposition to whatever it calls "evil"—and that "evil" maligns noble traits that enhance human flourishing and exceptional achievement. Slavish value systems sanctify humility, passivity, pity, lassitude, dependence, non-responsiveness, and procrastination. These “values” lead humanity down a path opposite from the one Nietzsche embraces. They sustain those who avoid the challenge of greatness, who shun danger, and who mindlessly conform. Slavish values encourage dependence on higher powers, keeping people in a helpless condition.”

2 comments:

Atheism— to me— is a Christian moral concept of black and white. You are either with them or against them. There is only one God—the Christian God. There are no others. In this colorless existence Nietzsche was an Atheist. However in color Nietzsche was a Dionysian. His discipleship to this Greek god was an affirmation to life, and in direct opposition to the “no” of Christian morality. From his own pronouncement in his writings he was a disciple to this god. So by the definition of atheism—he was not one. His conception of Greek myth and their gods sprang from his classical studies and, for brevity is too complicate to discuss here when contrasting against Christian morality and their God, however it is vividly colorized in opposition with the black and white and to that of Christian morality and God.

Thank you, Anonymous. . .

But did Nietzsche believe in gods as the average Christian would believe in them, as supernatural, all-powerful and spiritual beings, or did he believe the Greek pantheon was loaded with enlarged or magnified human beings with human faults and virtues which we could study and emmulate for ways to become more empowered and enlarged ourselves? The latter would make him still an atheist by my definition of atheism, but I am not asserting this, only suggesting it.

Post a Comment